Gujarat Declared Free Of Open Defecation A Year Ago. But In 4 Districts, Toilets Without Walls, Water And Unconvinced Locals

Vineshbhai Pawar and his wife Savita beside the toilet built for them under Swachh Bharat Mission in Koshimpatal village of Gujarat's Dang district. The toilet does not have a door or a pot, forcing the couple to defecate in the open. One year after Gujarat was declared free of open defecation, our journey through four districts revealed the declaration was premature. We found toilets without walls, without water, unconvinced locals and faulty verification.

Valsad, Dang, Dahod, Chotta Udepur (Gujarat): Under a mango tree, a one-minute walk from his house, farmer Kishanbhai Mawi pointed to the government-built, Indian-style squat toilet that he, his wife, 21-year-old son and 16-year-old daughter never used.

It was easy to see why.

The toilet is a ceramic hole in the ground, without walls, running water or connection to a sewer. It is connected to a cess pit, but that has been of little use. It has been 24 months since the toilet was built gratis for them, but Kishanbhai and family do what they have always done: Squat in their field.

"We have been planning to finish it, but I have not been able to save enough money," said Mawi, "Sometimes we cover it and use it as a bathroom, but it is largely useless."

Such unused toilets are common across Jogvel, a village in the Valsad district in southern Gujarat. In at least four districts of his home state, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's flagship programme, the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Mission, or SBM, is plagued by unusable toilets, a lack of water to flush them and widespread resistance to changing the open-defecation habit.

On October 2, 2017, Gujarat became the sixth state to be declared to be open-defecation free (ODF). The state's 18,261 villages were verified to be ODF three months after the declaration, and no more than four were yet to be verified six months later, according to the latest available data on the Swachh Bharat website. The state built 3.18 million toilets since the launch of the SBM on October 2, 2014, the 145th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi.

We visited 12 villages across four districts and found the claim to be obviously untrue. We selected these four districts because a September 2018 report from the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), the government's auditor, found multiple infirmities in that claim.

This story continues a FactChecker series evaluating the government's flagship programmes in the run-up to the 2019 general elections. The first of this series investigated the government's rural-jobs programme (here, here and here); the second spoke about the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Mission's sewage problem, the third (here, here and here) evaluated the Pradhan Mantri Sahaj Bijli Har Ghar Yojana (The Prime Minister's electricity-to-all-homes programme), and the fourth, the fudging of ODF data and shoddy toilet construction--amid evident enthusiasm--in Uttar Pradesh, set to be declared ODF on December 31, 2018.

Holes in the ground

There appears to be substantial variation between the government's claims and reality. For instance, in Valsad district's Kaprada taluka (where Mawi lives), 98.73% of the toilets were unused, said the September 2018 CAG report.

Kishanbhai Mawi (left), a farmer from Jogvel village in the southern Gujarat district of Valsad, and his family still defecate in the open because the toilet (right) constructed for them by the government in 2016 has no walls, water, door or roof.

Farmer Mawi is better off than most in his village. His toilet may not have walls, water, door or roof, but it is embedded in cement. Other households in Jogvel got just a toilet pot or a door.

Factory worker Shirish Chaganbhai of Jogvel said that in 2016 he was asked to dig a hole that would serve as a toilet pit. He never got his toilet from the panchayat, or local village council.

"They (panchayat members) keep telling us that they will construct the toilet soon," he said. "My parents are old. They have trouble going outside to attend nature's call, but they don't have a choice."

Of the defunct toilets in Kaprada, only 14.5% were newly constructed and put to use since March 2018. A "significant number" of households were either without toilets or not able to use them because they were incomplete or did not have water, said the CAG report.

FactChecker requested comments from the state coordinator for sanitation, Deepak Joshi, visiting his office, sending an e-mail and calling his office five times over two weeks. There was no response. This story will be updated if and when he responds.

Water shortage limiting sanitation efforts

To the north of Kaprada in Dahod district, a widespread shortage of water was a major deterrent in stopping open defecation. Santuben, a labourer from Gadoi village, had her toilet built under the SBM two years ago. Since it was difficult to get water to keep the toilet clean, her family uses the toilet only during the monsoon.

Santuben, mother-in-law and son (left) in the eastern Gujarat district of Dahod have locked up the toilet (right) constructed by the government outside their home because there is no water. They use it only in the monsoon.

The husband of the village head or sarpanch, Rameshbhai Mansingh, who functions as the de facto sarpanch, said that toilets were constructed in around 700 of 1,200 village houses. But less than 40% are used.

"A severe water shortage has made many of the toilets useless," said Mansingh. "The villagers are struggling for drinking water. It gets difficult to convince them to use more water everyday for the toilet when they can just use less water and defecate in the open instead."

In an earlier investigation by FactChecker in this series, we quoted a August 2018 CAG report that said 83% of rural Indian households rely on community water sources. Every village in Gujarat may not suffer the water shortage that Gadoi does--it was the only one that did of the 12 we visited--but it reiterates a frequent finding that toilets without water are useless.

A battle between contractors and local officials

In April 2017, when the government constructed a toilet for agricultural labourers Kevaben and Ramanth (they both use one name), they were happy that they had a toilet for the first time ever. "We did not have to go to our farm at night to answer nature's call anymore," said Ramanth, "And we could defecate without being scared of snakes or other insects."

After using it for a year, Kevaben, Ramanth and their two children in the Ghoghli village of the southern Dang district have now switched back to defecating in the open.

"One morning, I entered the toilet and was just about to squat when the tiles I was standing on sank and the walls bent towards me," said Ramanth "I rushed out and the toilet completely collapsed."

Ramanth and Kevaben, agricultural labourers with their two children at Ghoghli village in Dang district. On the right, the remains of their collapsed toilet. They used it for a year, until, one day, the floor caved in and the walls fell apart.

Other toilets in Ghoghli are standing--just about.

Home-maker Savitaben (she uses only one name) showed us her detached door and said her family believes it is a matter of time before it collapses. The village chief, Sonubhai Bhure, said two contractors constructed the village toilets. Savitaben said toilets built three years ago were in better condition than ones made a year ago.

Left: A toilet built three years ago in Ghoghli village of south Gujarat's Dang district. Right: A toilet constructed a year ago is in worse shape.

About 5 km from Ghoghli in the village of Kasavdahad, the situation is similar. Arvind Sareng, a farm labourer, stopped using the toilet built by the government after the walls of his neighbour's toilet collapsed. His family of five used the toilet for two months and ever since the neighbour's toilet collapse, they are back to defecating in the open. "This seems too dangerous," said Sareng "I would rather go out than get injured in the toilet."

The rickety toilets are a consequence of friction between panchayats and contractors, said Dinesh Kanshu, chief of Dabdar village in Dang district, and the eagerness of contractors to get hold of the Rs 12,000 that is supposed to be transferred directly to a beneficiary's bank account but gets to the contractor's account instead.

Half-built toilet in Dabdar village in the Dang district. The contractors wanted to be paid first; officials told the sarpanch to ensure the toilets were built first.

In Dabdar, the sarpanch and the contractors had a feud three years ago, and toilet construction stopped. The contractors stopped working because they wanted full payment. Kanshu said taluka officials wanted contractors paid only after they built the toilets.

There is another reason why there are not as many toilets as there should be: Data that are not updated because there are no follow-ups.

Old data, slow--or no--follow up

Dabdar village in the Dang was declared ODF on September 27, 2016, with toilets constructed in all 142 households. The CAG report said the administration declared the villages and the districts ODF based on a baseline survey conducted in 2012. The list of beneficiaries was not updated after the survey and so many households were left out.

The sarpanch of Dudhiyadhara and Umedpura villages in eastern Gujarat's Dahod district, Nanubhai Bhuriya, told FactChecker that while both villages were declared ODF, about 25% of the households did not have toilets.

"I was given a list of beneficiaries and we got toilets made for all of them," he said. "Since the target was completed, the village was declared ODF. Three months ago, I submitted a list of the remaining households at the taluka headquarters but I have not received a reply."

"We did get the list and I have got the information that the government plans to allocate a new grant for the people who have been left out," said JR Rathwa, Limkheda taluka development officer, "I don't know when we will get the grant, but it will be soon."

In 120 villages test-checked by the CAG, 29.12% of the households in eight districts did not have access to toilets. As of June 2018, as per the district administration's response to a request filed under the right to information act, 140,000 families were yet to get toilets under the SBM-Gramin (rural) scheme in Dahod.

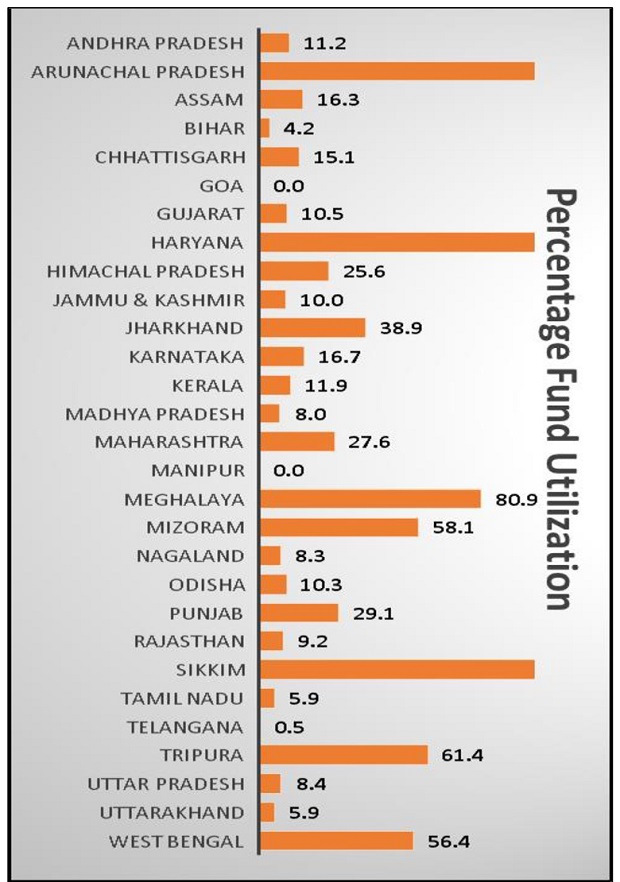

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General of India report, September 2018.

Then there is the most basic problem of all--many people do not want to change their defecation habits.

Resistance to changing behaviour

In the village of Kevdi in the eastern Gujarat district of Chhota Udepur, we saw government-built toilets covered and converted to bathing areas. These families had twin-pit toilets--toilets that have two connected cesspits which let water seep out and keep sludge in. Each pit is good for about three years; once one pit is filled, it is blocked and other pit is used. The sludge in the blocked pit decomposes in three years, so it can be removed and used as fertiliser, freeing up the pit for sewage again--which were in relatively good condition along with access to water supply.

Vikram Jitenbhai, 18, and his family of seven have a toilet inside their house, but they refuse to use it, as they don't want to "dirty the place they live in".

Vikram Jitenbhai and his siblings (left) in eastern Gujarat's Chhota Udepur district covered up the pit of the toilet (right) constructed under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan in May 2017. The family now uses the toilet to take baths and continues to defecate in the open.

In eastern Gujarat's Dahod's Nani Zari village, Chatrasingh (left), a labourer, and his family continue to defecate in the open because they don't want to defecate close to where they live. The toilet the government built for them (right) is covered with cobwebs and dust.

Since the launch of SBM, the ministry of drinking water and sanitation has issued guidelines that require 8% of the total national allocation for SBM-Gramin to be allocated for Information, Education and Communication (IEC) strategies. Of this 8%, 5% is to be used by the states and the same amount is to be matched by the state government.

Using the money allocated under IEC, the government should conduct several campaigns to make locals aware of the need to use toilets, spread information, help build skills and monitor toilet building and use. Further, 60% of the funds allocated for IEC should be spent on interpersonal communications. However, the states are not utilising these funds to the full, government data show. Gujarat used just 10.5% of the allocation in the year 2016-17.

Source: IEC Guidelines for States and Districts

"People in rural areas have been defecating in the open for 40-50 years, even longer," said Bindiya Patel, programme manager at Mahila Housing Sewa Trust (MHST), an advocacy, "So, they face a lot of mental blocks when, one day, they are asked to start using toilets."

In two villages in the central district of Bharuch, the MHST conducted what they called "routine interventions" forming a community action group and conducting training sessions to create awareness about toilet use. The group's members were trained to interact with the local government, voice concerns and were provided with basic technical training. Patel said both villages (Talodra and Dadheda) showed "tremendous progress" and have become "completely ODF", although we could not verify that assertion

"Only constructing toilets is not enough," said Patel. "There needs to be a persistent and continuous effort to make people aware and break their inhibitions."

This is the third part of a set of stories investigating the Swachh Bharat Mission. You can read the first part on the sewage problem of the national toilet-building scheme here, and the second part here.

These stories are part of a series evaluating flagship government programmes in the run up to the 2019 general elections. You can read a set of stories on the rural jobs programme here, here and here, on the rural electrification programme here, here and here.

(Shreya Raman is a data analyst with IndiaSpend and FactChecker.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.